Foster Kids Should Be Supported by Stronger Communities

Cardinal Team

Foster Kids Are Constantly Moved Around

Our foster care system devastates kids’ lives by uprooting them from their communities. These children are being shipped out of state. Some are moving to dozens of different living situations throughout their years in the foster care system. To be fair, the DHHR usually has the stated goal of keeping kids in their communities. However, many communities lack the support systems to keep children in local homes.

The bleakness of the foster care system is not primarily a failure of the state – but of the community and the individual. The government cannot give children a loving home. Only families and communities can do that. Many kids are in bad situations because their communities and the adults intheir lives have failed to take responsibility for these kids’ care.

As I mentioned in my last post on foster care, West Virginia has been shipping kids out of the Mountain state to a facility in Pennsylvania. What these kids endured at this out-of-state facility is tragic. The amount of abuse and trauma faced by foster kids in general is alarming too. One often overlooked trauma is how kids are often bounced between dozens of living situations.

There Isn’t Enough Community Support for Foster Kids

As noted above, social workers generally do try to keep a child close to home. However, they cannot do so if there are not enough foster parents in the area. There are also less likely to be foster families in communities that lack any support structures for foster families. This could be at school, non-profits, houses of worship, etc. Social workers cannot force families to take in children. It must come from good people who want to care for children. What if, we began a movement of foster-care-friendly schools, churches, community centers, and other organizations?

In a CBS report, Carnell shared that he was moved to about 30 different living situations during his time in foster care. He shared that this instability devastated any relationships he might have had. He shared, “Try not to get too attached to people. A lot of friends – I have no one that I can really call my friend.”

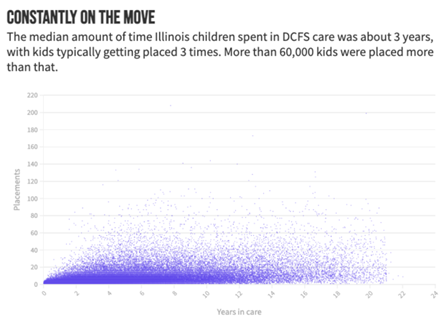

This story is tragic, but the data suggests this is not an isolated incident. In Illinois, the Department of Children and Families (DCFS) keeps data on child placement – and how often they are relocated. CBS put together the graphic below. As the graphic shows, in Illinois at least, it is not uncommon to see kids placed in 50, 60, or more places before they age out of the system.

Reunification vs. Stability

When kids enter foster care, the ideal outcome is for them to reunite with their biological families. In No Way to Treat a Child, Naomi Schaeffer Riley recounts how in the 1850s a Christian minister saw needy children on the streets and formed a movement to ship these kids to farms in the Midwest. Riley writes,

Despite the fact that many of these children had living parents, the Children’s Aid Society began sending thousands upon thousands of them to work on farms in other parts of the country. It was seventy-five years and 200,000 children before the orphan trains ended, partly the result of a decreasing need for farm labor.

Riley notes that today the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction. The idea of separating families provokes anger in many people. It’s also true that, as Riley points out, “Not all parents have the same good intentions regarding their children, though. Some even wish them harm.”

Foster Kids Should Be Cared For As Individuals

We should treat every case individually. The child’s well-being should be placed first with the hope of reunification if it does serve the child. Communities are in a unique place to serve in this capacity. Communities should be equipped to help these kids, so they don’t need to either go as far or keep getting moved around. Not only communities but more of us as individuals, even if we don’t become foster parents, should think about how we can care for children not our own. Even if it is a small act like volunteering at a Big Brother Big Sister organization, we can bring some light and joy to the life of a child who is suffering.

Who Should Be A Foster Parent?

I recently came across a story on social media where a woman shared that she and her husband were being pressured to take in the husband’s niece who was otherwise going into foster care. She shared that due to her husband’s demanding job it would fall to her to raise a child that was not her blood nor had she ever met. She wanted to know if she was selfish for not wanting to raise someone else’s child.

I don’t know if this story is true, but there are certainly people in similar situations asking similar questions. “Is someone else’s child my responsibility?” I would suggest that this woman is not obligated to care for the child, but her unwillingness to do so is also not particularly noble. If she became the caregiver for her husband’s niece, she likely would resent the child. She might take out her resentment on the child. Her reasons for refusing to take in the child are valid. However, she should also face the reality that her niece will face a hard childhood in the foster care system.

Time to Consider Community Supports for Foster Kids

This article is not a call to condemn other people for their inaction on behalf of children in foster. Nor is it meant to say we should all become foster parents. Some of us are not prepared to raise a child who has already faced severe trauma. Realizing this is a healthy way to understand our own limitations and consider how we can help these kids. Instead, this article is an invitation to reflect inwardly on our motivations and ability to help children in our communities. How can we personally serve these kids and help our communities become a place where kids can find refuge over the long term?

Nate Phipps is the Communications & Social Media Associate for the Cardinal Institute for West Virginia Policy.