Drive Times to Methadone Treatment Among Medicaid Patients

Cardinal Team

President Biden Announces National Recovery Month

Recently, President Biden announced that September is National Recovery Month.

“In celebration of Americans on the road to recovery, this National Recovery Month we recommit to helping prevent substance use disorder, supporting those who are still struggling, and providing people in recovery with the resources they need to live full and healthy lives,” President Biden said in the press release.

Over the past two years, the Biden Administration has worked to make growing access to opioid use disorder treatments through mobile units a policy priority of the Biden-Harris Administration.

However, many rural states fail to reap the benefits of the proclaimed “helpful” policy. Recently, the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved from Johns Hopkins University Press released eye-opening data. ‘Drive Times to Methadone Treatment among Medicaid Patients’ explores the effects of treatment moratoriums for mountaineers. This all-new research quantified the time patients traveled to receive methadone treatments.

West Virginia Needs Methadone

Methadone, the primary means of treatment for opioid users, is a pharmacotherapy. This treatment option has allowed those who receive it to be five times less likely to have illicit drug use, alcohol use, and criminal involvement than those who do not.

In 2015, West Virginia reported 41.5 deaths per 100,000 individuals due to addiction. From 2015 to 2016, there was a 20% increase in the occurrence of overdoses. This makes overdoses the sixth leading cause of death in West Virginia.

“Despite the existence of medication for opioid use disorder, nearly half of patients with the condition do not receive treatment,” said Regina LaBelle, Director of the Addiction Policy Initiative at the O’Neill Institute and co-researcher of ‘Drive Times.’

Methadone Treatments Are Difficult to Get in Rural Communities

According to the study, fewer than 1,700 opioid treatment center (OTC) locations exist in the country. Consequently, most of those who live in more rural counties have disproportionately greater travel times to OTC facilities than others—a population impacted by inadequate provider availability across the board.

At least 48 million Americans live in primary care or mental health provider shortage areas. In West Virginia, 1,146 Medicaid enrollees met the inclusion criteria for the research.

Drive Times are Long for Medicaid Patients in West Virginia

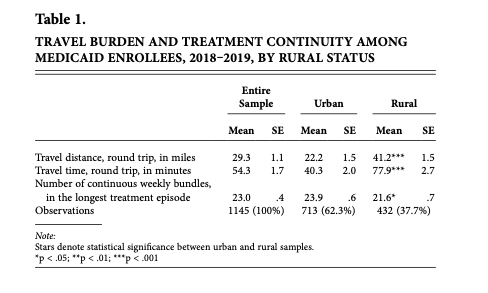

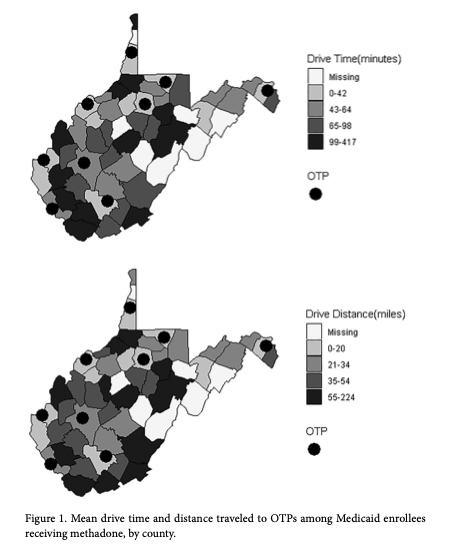

“Across the entire sample, methadone patients traveled an average of 29.3 (SE: 1.1) miles round trip for their treatment (Table 1), with a mean drive time of 54.3 (SE: 1.7) minutes. Those living in rural areas experienced much longer drive times, with a mean round trip drive time of 77.9 minutes compared to 40.3 minutes (p<.001) for those in urban areas. Rural residents had worse treatment continuity with a mean of 21.6 weekly bundles in their longest continuous treatment session, versus a mean of 23.9 (p<.05) continuous weekly bundles among more urban residents,” LaBelle found.

“Medicaid enrollees receiving methadone in a largely rural state drove about an hour per round trip, on average, to get their treatment. Those living in more rural counties were subject to a significantly greater travel burden, traveling about 20 more miles and 40 more minutes per round trip compared to those living in more urban areas.”

“Given that the mean travel distance to a methadone clinic in our data was about 30 miles, it is likely that many patients who would benefit from methadone therapy are going untreated.”

“To capture the true challenge of connecting to care, future work should also consider hidden travel costs, such as the need for childcare, time away from work, and gas prices. Against the backdrop of the opioid epidemic, made worse by the recent COVID-19 pandemic, policymakers and researchers alike should prioritize work that will help eliminate barriers to necessary OUD treatment.”

Certificate of Need Laws Strike Again

The cause of such wait times and interruption of care is best explained by one of West Virginia’s old, outdated regulatory barriers: Certificate of Need. CON laws, first created in the 70s, require healthcare providers to obtain permission from a government entity before expanding facilities, offering new services, or purchasing certain pieces of equipment. In addition to the already egregious barriers to care, the state has also enacted a moratorium on building new opioid treatment centers in West Virginia.

For example, in 2017, the Beckley Area Medical Clinic (BAMC) applied for an exemption from the CON application and approval process through the West Virginia Health Care Authority’s (HCA) CON Board.

The Exemption Application, filed by the clinic, stated “…we will also be providing substance abuse treatment by prescribing buprenorphine products…We will be using the exemption as part of the application process to be a licensed office-based medication-assisted treatment (OBMAT) facility.”

At the time, the BAMC was an existing practice that had been prescribing buprenorphine products for substance abuse. Yet, the passage of a new law required OBMAT facilities to receive a CON through the state’s Health Care Authority, regardless of the facilities’ previous operation.

On April 18, 2017, after a $1,000 application fee, the clinic received a letter of denial to stay open from the HCA due to the “failure to address behavioral services that would be provided.”

BAMC no longer has an OBMAT facility and there is no clinic in Beckley offering substance abuse treatment with buprenorphine.

Time for a Change

West Virginia has the highest statistics on overdose rates in the nation. This should motivate policymakers to prioritize harm reduction and drug treatment. It is beyond time to lift the moratoriums that have limited the number of life-saving treatment centers across the state.

Jessica Dobrinsky is a Policy Analyst for the Cardinal Institute for West Virginia Policy.