Civil Asset Forfeiture in West Virginia

Cardinal Team

Seizing Freedom

On February 19, Nevada police pulled over Stephen Lara. Lara consented to a search of his vehicle, where police discovered almost $90,000 of cash in a backpack.

“I don’t trust banks, so I keep my own money,” he said. “I have nothing to hide from you.” Police did not arrest or charge Lara with a crime, but officers seized the money on claims that the money was for drug trafficking.

“You’re taking money out of my kids’ mouth,” Lara proclaimed.

On December 7, more than $100,000 was seized from a bag at Dallas Love Field Airport after a canine alerted police. Police did not arrest the owner of the bag. There are currently no updates about whether authorities will return or keep the funds.

Though, Nevada has agreed to return sequestered money to Lara. Unfortunately, these two cases are only a glance into the abuses of power that many Americans have become victims of.

Civil Asset Forfeiture Encourages Policing for Profit

In 43 states, police and prosecutors can keep upwards of 50% of proceeds taken from civil asset forfeiture. Unfortunately, these laws put the property of innocent individuals at risk and encourage law enforcement officers to “police for profit.” A study by the same name, released by the Institute for Justice (IJ), determined billions of dollars are forfeited every year.

Civil asset forfeiture hoped to burden criminal enterprises by removing resources that allowed such crime to continue. However, this system has effectively used this tactic to fill bottom lines.

The Costs of Civil Asset Forfeiture in West Virginia

West Virginia, specifically, reported forfeiture revenues totaling $2.3 million between 2009 and 2018. 100% of forfeiture proceeds go to law enforcement in the Mountain State. Additionally, between 2000 and 2019, West Virginia police agencies generated an additional $70 million from federal equitable sharing. Federal equitable sharing allows state and federal law enforcement authorities to share liquidated seized assets. Local and state law enforcement often use this to bypass state laws that restrict forfeiture.

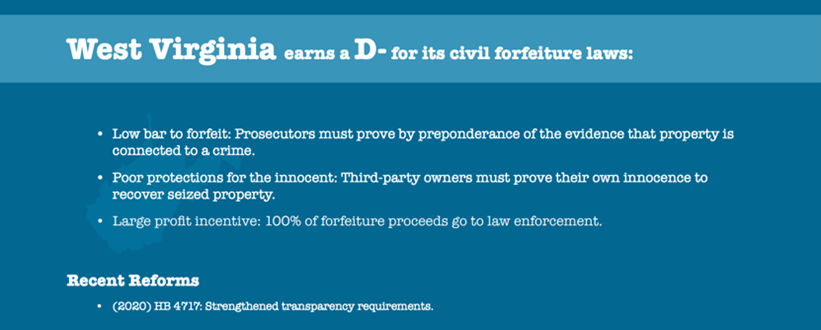

IJ’s civil forfeiture law rankings awarded West Virginia a D-. West Virginia’s only evidentiary requirement to seize is a preponderance of the evidence, a burden of proof that is met when police can convince a court that there is more than a 50% chance that the claim is valid. For an innocent owner to reclaim their property, West Virginia forces owners to prove their innocence to law enforcement.

Civil asset forfeiture is an explicit denial of the fundamental American principle “innocent until proven guilty.” Individuals who find themselves in these circumstances face a severe deprivation of due process.

In 2018 a State Trooper in West Virginia issued a driving warning to Dimitrio Patlias and then proceeded to take his $10,000 in cash. The officer accused them of having drugs and fraudulent gift cards. Patalias and his wife returned to their home with only $2. Thankfully, a few weeks later, an officer returned the possessions in full to the couple.

Time for Reform

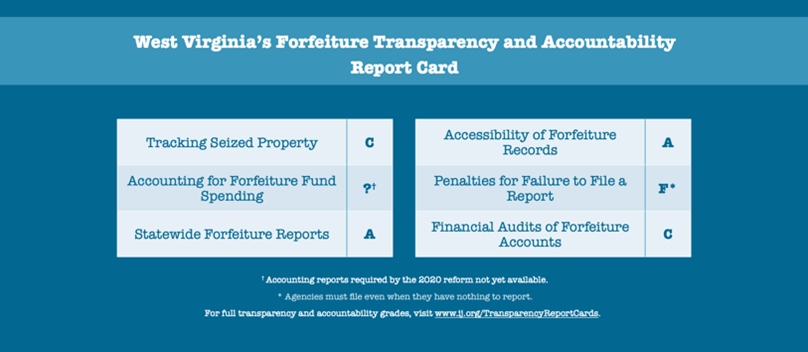

West Virginia State Code §60A-7-708 (10)(b) helps to improve this suspicious activity by requiring any law-enforcement agency or office in the state to report any property retrieved through asset forfeiture to the State Auditor. In 2019, House Bill 2563 attempted to resolve issues not addressed by the current Code, requiring a conviction before any property may be taken by law enforcement and prohibited the proceeds of these seizures from going to law enforcement, correcting the incentives to police for profit. Unfortunately, the bill did not pass.

Civil asset forfeiture is an explicit denial of the fundamental American principle “innocent until proven guilty.” Individuals who find themselves in these circumstances face a severe deprivation of due process. West Virginia must continue to reform these egregious laws to restore constitutional protections and remedy inequalities for everyday Mountaineers.

Jessica Dobrinsky is the Policy Development Associate for the Cardinal Institute for West Virginia Policy.