What is a certificate of need?

Certificate of Need (CON) laws are regulatory impediments instituted in thirty-five states requiring many health care providers to receive authorization from the state’s health regulatory board in order to open a new, or expand, an existing health facility.

CON is unlike some health regulations which ensure facilities meet quality standards to improve care and promote safety. Instead, CON determines a necessity for services based upon anticipated investments of prospective providers and possible commercial impact on existing providers.

Thus, for a CON to be issues, eager providers must argue a need for their business to function or expand. The application process is lengthy and onerous. Fees for the application vary. Determination of admissibility may take a month or longer. The CON process also allows incumbent providers to intervene in the application review. Other providers can propose arguments for why applications should be denied. In the case of a CON denial, providers are forbidden from establishing or expanding any health care facility or service. And, unfortunately, the health regulatory board is not required to indicate a reason for denial.

How did we get certificate of need?

Originally proponents claimed CON programs would be an effective means to reduce costs and promote equal access to care. Proponents also alleged that these new guidelines would efficiently reduce mortality by protecting high-volume, skilled care facilities across the states.

In 1964, New York became the first state to endorse CON programs throughout their municipalities. In 1972, Section 1122 programs, a segment of the Social Security Act (SSA) of 1935, encouraged a regulatory review process for large capital expenditures in the states.

The SSA allowed the federal government to withhold Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements for capital expenditures not approved by state planning agencies. Therefore, states began to adopt various review methods so that reimbursement payments would still stream to states.

Then, in 1974, the National Health Planning and Resources Development Act passed. It offered exclusive federal funds for health market review. Early stages of this CON process permitted the assessment and regulation of expenses totaling more than $100,000, bed additions, and service expansions for hospitals and nursing homes. By 1975, 46 states had opted into some form of a review program. By 1980, 49 states had fully enacted a CON process.

The Development Act dispensed nearly $150 million in annual funding for health planning in its prime. Yet, in 1987, a bipartisan federal government repealed CON, confirming that the program failed to resolve the issues it sought to resolve. This federal repeal caused many states to eliminate or modify their review programs. Unfortunately, West Virginia chose to continue their CON program.

Why is it necessary for West Virginia to repeal certificate of need laws?

CON laws are directly related to cost, access, and quality of health care.

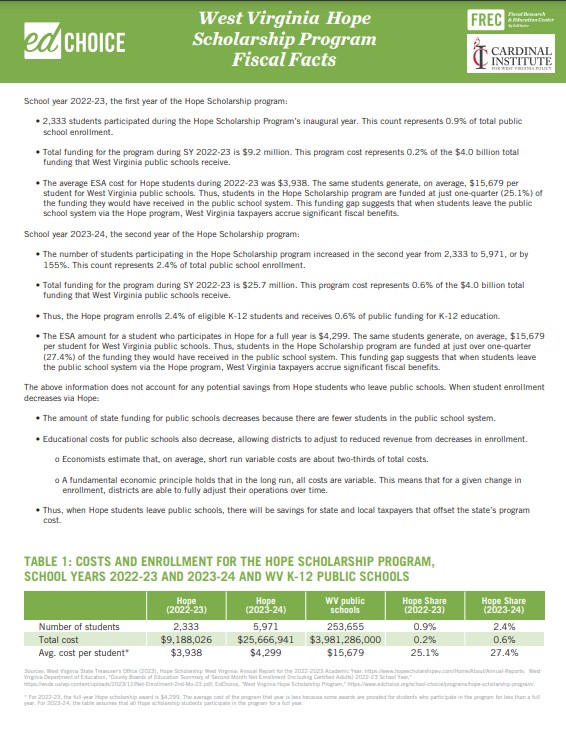

60% of the US population lives in a state that has CON laws. These same states also have 30% fewer hospitals per 100,000 residents. The most frequently regulated services by CON requirements are nursing homes, psychiatric services, and hospitals.

The Kaiser Family Foundation’s most recent study found that states with CON laws in place have healthcare costs 11% higher than states without these policies. Moreover, the Mercatus Center at George Mason University discovered a 5.5% higher mortality rate, fewer hospital beds (131 fewer per 100,000), fewer MRI machines, and less access for CT scans.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) have also documented the damaging impacts of CON. In a 2016 report, the two agreed that “it is apparent that CON laws can prevent the efficient functioning of health care markets.”

In West Virginia, the ability of CON to restrict new businesses and services means that rural residents must travel further to get to a provider, wait longer for appointments, and, as seen in the table above, pay more for the health care they receive.

Government shouldn’t have the ability to require businesses to prove a need for their services. This is particularly true in a state urgently in need of high-quality, affordable health care.

Jessica Dobrinsky Harris is a Policy Analyst for the Cardinal Institute for West Virginia Policy.